Shopping center landlords want to preserve flexibility and their tenants want to protect what they “bought” when signing their leases. Ruminations believes both positions deserve respect.

Shopping center landlords want to preserve flexibility and their tenants want to protect what they “bought” when signing their leases. Ruminations believes both positions deserve respect.

If a tenant wants to be the master of its own destiny it shouldn’t be a tenant where others live. It should either buy its own homestead or do the equivalent of a sale-leaseback where it can generally write its own lease. If, on the other hand, a tenant wants the benefit of a “community” it has to yield some autonomy. Someone has to manage the community, and that manager inevitably is a “landlord.”

On the other hand (“he wore a glove,” but that’s the punchline to a clean joke not worth telling today) landlords demanding total management control need to be benevolent dictators, and in the long run, there are no such persons. Sometimes, a benevolent dictator needs to subordinate her or his own interests to those of his or her “subjects.”

Even if a landlord shows all of the signs of being a benevolent dictator, there is the “little” issue of “trust.” We haven’t yet met a tenant who completely trusts its landlord to “do no harm.” Unsurprisingly, we haven’t yet met a landlord who completely trusts its tenants to subordinate their immediate interests to the long term interests of the entire property. And, even if each party actually had a sufficient quantum of trust in the other, there is the “little” matter of each party having a legitimate, but sometimes alternate, view of the effect of any suggested change to the property (e.g., to the shopping center).

For the handful of readers who haven’t yet caught on today, we’re writing about “site plan control.” That translates to whether a tenant should be able to have a say as to landlord-chosen changes to the overall property. And, we’re thinking about changes entirely initiated by a landlord as well as changes designed by a landlord in response to government actions.

Ruminations will suggest some guidelines in an attempt to create a starting point for discussions between a prospective tenant and its prospective landlord. We’ll be framing those in the context of a shopping center environment. Though bargaining power (one of our screeds or mantras) overhangs all such discussions, we’ll pretend that the shopping center is in the state of Utopia. In Utopia, landlords and tenants want to accommodate each other’s legitimate interests.

Our thinking is that there should be two categories of site plan changes: “can’t do” and “can do, but reasonably.” Unfortunately, like life itself, there are no clear lines and the “can’t dos” morph into “can dos, but only if reasonable,” and then into “tenant, get real, leave us alone.”

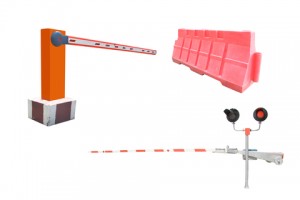

To have any of this make sense, we need to step back and think about what a tenant should get for its rent and its other promises given to its landlord. For sure, by definition, a tenant is entitled to exclusive possession of its premises. We leave for another day an exploration of the kinds of things landlords should be allowed to do within their tenants’ premises during the lease’s term. But, what about the “things” that fall outside of the premises for which a tenant is also “paying”? Here’s a stark example before we trudge onward. Isn’t a tenant entitled to an unencumbered entranceway, one without a new security bollard directly in front of it? If a tenant, any tenant, asks that its landlord, in the lease, promise that the area in front of the store’s customer entrance be unencumbered, shouldn’t the landlord’s knee-jerk reaction be “sure” and not “no way, trust us – we would never do that”?

At a minimum, customers should be able to enter and leave the shopping center. That, however, is not enough. When a tenant first sees the center, it will see whether the access is “good” or just “sufficient” access. It will see whether its customers can enter from the main road and whether the shopping center entrance is proximate to the proposed premises. Those things make a difference. Assume, for the moment, that there are two pizza restaurants at the property, one quite some distance from the other – enough so that there is adequate business for both. Suppose again that there are separate shopping center entrances leading to each of them. Wouldn’t it be a legitimate concern on the part of each of those pizzeria owners that the landlord not relocate “its” entrance, thereby forcing customers to enter nearer to its competitor such that the customers will make the now, more convenient, choice? Ruminations thinks so.

Now, you would ask, “Why would a landlord spend money to voluntarily relocate a shopping center entrance?” Try this: “to attract a large tenant who wants the entrance relocated.” Yes, burn an existing tenant and destroy that tenant’s business. We’re not saying that in response to a prospective tenant’s request for such protection, it isn’t legitimate for a landlord to negotiate for a pre-approved location for a possible replacement entrance. At least that would allow the prospective tenant to choose to accept such a risk of where the relocated entrance might be located. That same approach could be applied to involuntary relocations as well.

Readers should have a sense of where we are going.

Basically, as Ruminations sees it, when a tenant leases a particular space, it gets a package to go along with the space itself. It has “bought” the access and visibility that it sees when the lease is signed. Just as a landlord shouldn’t be allowed to reconfigure the interior of the premises – the “picture” so to say – it shouldn’t be allowed to reconfigure exterior features that are key to the chosen location – the “picture frame,” so to say. And, access not only means for customers; it means for deliveries and trash removal as well. Visibility means of the storefront, the customer entrances, and the agreed-upon signage locations.

Now, not all of these external features are of the “highest” level. Some are so critical that a landlord shouldn’t touch them unless its tenant agrees and the tenant should have carte blanche in deciding whether to assent or not. Such a “critical zone” simply might be a designated area surrounding the customer entrance. The principle behind a “critical zone” is that the tenant shouldn’t have to negotiate over whether its business would be upset; there are some things about which the tenant should be regarded as the expert-decisor. An example might be the need to protect a section of sidewalk from some point to the left of the premises until a point to the right of the premises.

The sidewalk example allows us to transition to “protected zones,” portions of the shopping center that are important to the tenant, but where the tenant has to accede to reasonable changes. That might include the sidewalks to the left and right of the critical zone. Tenants are entitled to a clear sidewalk in front of their stores and also to a clear path, of reasonable length, to either side so that customers have convenient access to the store itself. On the other hand, the need for a clear sidewalk path (in a typical, local shopping center) “way down at the other end” is doubtful. That leaves a portion of sidewalk, neither in the critical zone, but not so far away as to make tenant control over it laughable. We’d suggest that if a landlord wants to reconfigure that portion or allow sidewalk sales on that portion, it should get its “protected” tenant’s consent and the tenant would have to be reasonable. We’d label those sidewalk segments as part of a “protected zone.”

For those who need numbers, here’s an example. Designate the sidewalk in front of and 25 feet to either side of the store as a “Critical Zone”; designate the sidewalk 100 feet to the left and right of the Critical Zone as a “Protected Zone.” The rest of the sidewalk is for the landlord to do with as it pleases. If the landlord wants to reconfigure or block all or any part of the sidewalk in the Critical Zone, the tenant could arbitrarily deny its consent. For the sidewalk in the Protected Zone, the tenant would have to give its reasonable consent.

Now, Ruminations knows there isn’t anything fresh or revolutionary in today’s blog posting and it isn’t a roadmap to drafting site plan control language for a lease. But, don’t miss the point we are making, not about lease drafting, but about lease negotiating. Yes, the landlord’s livelihood and skill relate to being able to optimize the success of its property, in today’s examples, a shopping center. But, if a landlord really, really wants the absolute, unfettered right to do as it pleases with the property, it shouldn’t lease any portion of it. That’s because a lease isn’t a gift to the tenant, it is bought and paid for by the tenant who legitimately wants to optimize the success of its business. When you show a space for lease, you are showing more than its interior. Landlords are leasing the premises as well as the relationship of those premises to the entire property (shopping center).

Both the landlord and its tenant have a legitimate interest in every component of the shopping center. Just as the tenant’s interest as to the far left front corner of the property, 2,000 feet away from its store might be, how shall we say, “diminished,” the landlord’s interest in the color of the tenant’s interior walls might also be “diminished.” On the other hand, just as a landlord would have heightened concern over structural alterations when made by a tenant, a tenant would have heightened concerns over having its front door made inaccessible. There are many items in the typical lease where the landlord’s consent should be needed. For critical items, it is appropriate for the landlord to be arbitrary. For many others, as is typically found, the landlord should be reasonable. We think that’s no different when it comes to allowing a tenant to have some control over site plan changes.

One last point – even if given the right to arbitrarily deny consent, every party has to act in good faith.

A thoughtful post. Thanks Ira. Being on both sides of this equation, I have seen more cooperation since 2008 on these issues. Prior to that time, many tenants set up shop at their own peril as to access, relocation etc. On the other hand, in 2009-2011, many Landlords were laying down on their unequivocal NO responses in droves. It will be interesting to see how the trend morphs as the economy (hopefully) continues to move in an upward trend. Will it be the return of the Landlord’s fiat or something more in the nature of what you suggest – reasonable approaches to working together to achieve economic success for the tenants and for the Center as a whole?

Interested to see what other folks think….

“On the other hand (“he wore a glove,” but that’s the punchline to a clean joke not worth telling today)”

I’ve seen it updated to “he wore a ring”, including in Itzhak Perlman’s review of PDQ Bach’s “biography”.

Thanks as always for your post. I happen to work for a landlord who is mindful of tenant concerns and is thus able to get most of his tenants to respect the landlord issues. That obviously leads to a good relationship between parties who are generally bound together for many years.

I do have one thought or question concerning your very last point, about denial of consent. It is not infrequent that a party will “throw a bone” at another party by agreeing that the other can do a certain thing with approval at the “sole discretion” (or similar verbiage) of the first party. Does that in reality give the other party more than it would have had in the absence of any provision at all? Or would the “good faith” requirement come into play to the same extent even if there were no language about approval in the first place? In other words, should a landlord (the side that I am almost always on) not throw the proverbial “approval” bone if it can help it?