We doubt that our next paragraph, let alone the rest of today’s blog posting, will make much sense to readers who haven’t seen last week’s posting. So, if that means you, we suggest you click: HERE.

We doubt that our next paragraph, let alone the rest of today’s blog posting, will make much sense to readers who haven’t seen last week’s posting. So, if that means you, we suggest you click: HERE.

After receiving a number of “off-line” comments from readers, we took a look at the various types of rice in our pantry and found the following: Carnaroli, Jasmin, Wild Rice, Arborio, California Sushi, Basmati Light Brown, Brown Jasmin, Extra Long Grain Rice, Brown Rice, and a Rice Blend (something that offers the look of much more expensive Wild Rice, but, with some white rice in the blend, is not as expensive). Who knew? Yes, to the eye some of these types clearly are “white”; some are not; some are “different minds will differ.” Thus, an expert organoleptically examining our pantry’s selection, would call some versions “white” and call others “brown.” But, when these, other than Long Grain White Rice and the straightforward Brown Rice, were offered for sale, the merchants wanted them to be seen as something other than “white” or “brown” rice. Those two boring descriptions imply “commodity” rice. Carnaroli Rice, which by the way we highly recommend over Arborio rice, for preparing risotto, costs the consumer more even though its production costs might not support that “bump.”

Last week, we left off where the court ruled, in the case of an Indian restaurant, that the rice it was using, allegedly “Basmati” rice, was actually a form of “white” rice. The complaining Chinese restaurant had an exclusive use right banning the sale of white rice by any other restaurant at the mall. And, to repeat the core of the court’s finding:

There exists no ambiguity in the term “[w]hite rice—boiled or steamed.” … Simply put, the term “white rice” is not susceptible to more than one interpretation, and therefore, the intent of [landlord] and [the first Chinese restaurant] is wholly irrelevant. Accordingly, the parties are bound by the ordinary meaning of that language.

Now, that takes us to the situation with the Japanese restaurant at the same mall as the Chinese restaurants. [For those who don’t remember or thought they could just skip the “set up” in last week’s blog posting, there were two such restaurants at the mall, both owned by the same person.] The first (earlier) of the Chinese restaurants signed its lease about four years before the mall opened and also about four years before the Japanese restaurant signed its own lease. Before either restaurant opened, the owner of the Chinese restaurant wrote to its landlord and to the Japanese restaurant to point out that it, the Chinese restaurant, had the exclusive right to sell “white rice – boiled or steamed” and also had the exclusive right to sell a specified list of menu items.

In 2006, long before the 2018 court decision that triggered last week’s and this week’s postings, a court found that the Japanese restaurant had clearly violated the Chinese restaurant’s exclusive use rights. The following year, the Japanese restaurant closed. The 2006 court did not decide whether the landlord had any liability to the Chinese restaurant. In fact, it wasn’t until 2017 and then again in 2018, that the court decided this question.

The Chinese restaurant’s lease “provided that if the Landlord violated this provision the Tenant could elect to reduce its rent by forty percent as its exclusive remedy.” What the lease did not require of the landlord was to enforce the Chinese restaurant’s exclusive against alleged violators. So, basically, the landlord’s sole obligation was to include the Chinese restaurant’s exclusive use prohibition in the leases of subsequent tenants. In the case of the Japanese restaurant, it did just that. Thus, the landlord had not violated “this provision,” and the tenant did not have the 40% rent reduction remedy.

This didn’t deter the Chinese restaurant. It sought damages arising out of the landlord’s alleged breach of the duty of good faith and fair dealing implied in every contract. That would include a lease. [For a refresher of this legal doctrine, click: HERE.] Basically, the question before the court was whether absent an affirmative obligation in a lease to act, can a landlord “sit idly by and allow one of its tenants to violate the exclusivity rights which the landlord granted to a co-tenant”? Here, all the landlord did was to encourage the two conflicted tenants to “work it out themselves.”

So, what did the court think? After all, regardless of what Ruminations or any reader believes, at the end of the day, what matters is what the court decided. That is here:

Rhode Island case law on this subject is sparse. … However, to the extent that [the Chinese Restaurant] has a viable claim against [its landlord] for violations of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing, the Court is unable to find by a preponderance of the evidence that [the landlord] violated that implied covenant. The evidence before the Court is that when [the Chinese restaurant’s owner] complained to its Landlord about [the Japanese restaurant’s] alleged violations, the Landlord responded by working with both [restaurants] to resolve those disputes. … [The Chinese restaurant] contended that [its landlord] had a duty to evict [the Japanese restaurant] for violating the prohibition in its lease and selling items which were exclusive to [the Chinese restaurant]. Even if such a duty exists, and this Court is not convinced that it does, [the Chinese restaurant] had a corresponding duty to mitigate its damages. For example, [the Chinese restaurant] could have brought a third-party beneficiary suit much sooner than 2005. [The Chinese restaurant’s owner] testified that while he had concerns about [the Japanese restaurant], he was relatively satisfied with [the landlord’s] response up until 2005, when [the Indian restaurant] entered the food-court. It is only then that [the Chinese restaurant] commenced litigation. [Its landlord] failed to honor its commitment to join in that suit on behalf of [the Chinese restaurant]. However, by that time, [the landlord] had already violated Section 1.04 of the [the Chinese restaurant’s] Lease by entering into the [Indian restaurant’s] Lease. … As such, [the Chinese restaurant is] not entitled to any damages stemming from [the Japanese restaurant’s] violations prior to the commencement of this suit.

As long as we are at it, even though the court found that the Indian restaurant also had violated the Chinese restaurants’ exclusives, there would be no “double” rent reduction – a single 40% reduction was the limit.

The definition of “white rice” was not the only issue before the court. As was explained in last week’s posting, the second of the two Chinese restaurants at the mall was promised that no other restaurant at the mall (other than its own sister Chinese restaurant) would sell:

foods that are distinctively part of Oriental cuisine served in Oriental (i.e., Chinese, Japanese, Malaysian, Thai, Korean, Filipino, Vietnamese, etc.) restaurants and any foods or dishes substantially similar thereto in taste, appearance, style and/or ingredients, whether or not styled or denominated as an Oriental food dish. However, notwithstanding the foregoing, the incidental sale or use of rice as a side dish or ingredient shall not constitute a violation of Tenant’s exclusive, unless it is part of a [sic] oriental style food.

We suspect that most readers are now trying to decide if an Indian restaurant, as they think they know that cuisine to be, serves “Oriental” food. Here’s how the Rhode Island court looked at the question, one with which Ruminations agrees.

The court’s finding was that “the terms oriental style foods and oriental style restaurant lend themselves to more than one interpretation.” The Chinese restaurant’s lease actually identified three separate ways by which an item of food would be deemed as such. There was a list of specific menu items. It also referred to foods or dishes substantially similar “in taste, appearance, style and/or ingredients” to those menu items. Finally, the lease gave examples: Chinese, Japanese, Malaysian, Thai, Korean, Filipino, Vietnamese, etc. At the end of the day, to the court, each of these three methods was “far from clear and unambiguous.”

To begin with, the list of prohibited menu items began with: “including but not limited to.” The list included “rice” (and not just “white” rice). That would make any rice or rice-based dish an “Oriental” food. But, the prohibition against the serving of rice or rice-based dishes was “softened” by the caveat that “notwithstanding the foregoing, the incidental sale or use of rice as a side dish or ingredient shall not constitute a violation of Tenant’s exclusive, unless it is part of a [sic] oriental style food” demonstrates that serving rice, per se, did not make a restaurant “Oriental.” So, as the Chinese restaurant’s exclusive was written, one still needed to look at other ways to determine whether an Indian (and those restaurants do serve rice) serves “Oriental” food.

The Chinese restaurant’s lease’s list of what cuisines constituted “Oriental” cuisines was open-ended. While it specified certain nationality’s foods, it ended with “etc.” So, the list was not a closed one. This gave the court permission, as is does us, to look at a dictionary. This particular court chose The Random House Dictionary of the English Language (2nd ed. 1987). There it found that “Oriental” meant: “Pertaining to, or characteristic of the Orient, or East; Eastern.” That dictionary went on to “define the orient as: ‘a. the countries of Asia, esp. East Asia. b. (formerly) the countries to the E of the Mediterranean.’”

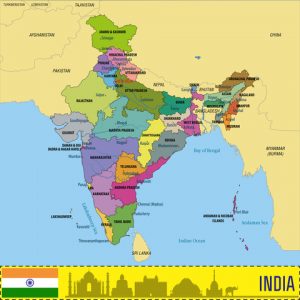

“India is a country of Asia and it is clearly east of the Mediterranean. Whether India can be considered Eastern is a more ambiguous question.” As Ruminations has previously written, a court’s choice of dictionary can change the outcome of a dispute. [If interested, click: HERE to see an example.] This time, the court looked at a second dictionary, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed. 2000), and saw that its definition for “oriental” was “[o]f or designating the biogeographic region that includes South Asia south of the Himalaya Mountains and Southeast Asia from southern China to Borneo and the islands of the Malay Archipelago.” By reason of its location directly south of the Himalaya Mountains, this definition would make India an oriental country. So, the court (and we) get little or no guidance from dictionaries.

What about “Oriental” foods being “any foods or dishes substantially similar [to Oriental cuisine] in taste, appearance, style and/or ingredients, whether or not styled or denominated as an Oriental food dish.” Without a “plain, ordinary and usual meaning,” that defined-term using definition provides no guidance.

Without unambiguous guidance from the words used in the lease, the court was released from the face of the document and became empowered to look for the “intent” of the parties when executing the Chinese restaurant’s lease. That’s what it did. Readers remembering last week’s blog posting will remember that the owner of the Chinese restaurant had been forced out of business at another mall when a new restaurant, owned by a person of “Chinese” descent, advertised itself as a “Cajun” restaurant but had a menu very similar to that of his Chinese restaurant there. The landlord was aware of this history and knew that the owner “was worried about other restaurants serving Chinese style food under the guise of a different label.” The agreement was to bar the sale of white rice. Apparently, “white rice is the staple Chinese food. Further, combination plates using white rice and other foods, particularly small pieces of chicken served in a sauce or fried in batter, are also crucial to Chinese style cuisine.” Further, the owner of the Chinese restaurant had complained about the dishes sold by the Japanese restaurant well before the Indian restaurant came along. Based on that negotiation and subsequent history, all before the appearance of the Indian restaurant, the court found that “at least some of the rice served by [the Indian restaurant] was similar in style, appearance and ingredients to oriental cuisine.”

In the case of the Indian restaurant, unlike in the case of the Japanese restaurant, the landlord was tagged with some liability. The difference was that for the Indian restaurant, the lease allowed that restaurant to sell “basmati” rice and, as we learned last week, the “rice” expert’s testimony was that basmati rice was “white” rice and the landlord’s express permission to serve basmati rice violated the Chinese restaurant’s lease.

So, after two weeks, what are our takeaways? We have only two. First, Lewis Carroll may have had it right when he wrote:

When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.” “The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” “The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

When writing (or negotiating for) an exclusive use right, we need to be very, very precise. The words used are critical. The people who wrote the Chinese restaurants’ leases thought they knew what was meant by “white rice.” They were wrong. Similarly, they thought they knew what “Oriental” foods were. They were wrong. We’ve seen this before when it came to “sandwiches” [click: HERE to learn more] and we saw this when it came to “groceries” [click: HERE to see what that was about]. Common sense consumer knowledge does not override accepted industry definitions.

Second, the way an exclusive use right is written is critical. What are the actual duties imposed on the landlord? Is it only to include a given prohibition in future leases? Is it to notify the allegedly offending violator? Is it to go to court? The list of possibilities is long, but absent spelling out those duties is not an enforceable list.

If anyone wants to plow through the Rhode Island court’s decision for herself or himself, it can be seen by clicking: HERE.

Leave a Reply