How long should it take to prepare the first draft of a lease that needs to include several (or more) “custom” business terms? We’re asking about those leases that need some thought, not the kind that can be prepared using a document assembly program. And, certainly not the kind that, in the future, will be “written” through the use of artificial intelligence (AI). [Yes, we are firmly in the school of belief holding that, not very long from now, machines will be preparing most first drafts, many subsequent drafts, and to many who depend on lease drafting to pay their bills, more final leases than you can now imagine. We even think that dueling AI systems will be writing a lot of leases and other agreements, unaided by humans, within as soon as five years.]

How long should it take to prepare the first draft of a lease that needs to include several (or more) “custom” business terms? We’re asking about those leases that need some thought, not the kind that can be prepared using a document assembly program. And, certainly not the kind that, in the future, will be “written” through the use of artificial intelligence (AI). [Yes, we are firmly in the school of belief holding that, not very long from now, machines will be preparing most first drafts, many subsequent drafts, and to many who depend on lease drafting to pay their bills, more final leases than you can now imagine. We even think that dueling AI systems will be writing a lot of leases and other agreements, unaided by humans, within as soon as five years.]

But, for now, when almost all leases are “handcrafted,” how long should the first version take? Obviously, it depends! But, we can all guess that those waiting for the lease think the time needed is a lot less than does the lease preparer. Brokers, often and especially, “think” “not very long, perhaps by later today or tomorrow.” Experienced owners and tenants trust those to whom the project is assigned. But, all of that sidesteps the question.

If any reader thinks that Ruminations has an answer, then that reader is giving us far, far too much credit. But, Ruminations does have a point to make. That point is: “Longer than most people think it should take.” We believe the real goal is not how long the first version should take, but how long the entire process should take. And, the time the entire process takes is very dependent on how much care and thought has gone into the first version. We’ll repeat that: It depends on how much care and thought has gone into the first version.

Almost every deviation from standard or customary business terms affects several or more provisions of a well-crafted lease form. Non-standard provisions are an invasion into that form. Care needs to be taken to avoid not only conflicts and ambiguities, but also unnecessarily contentious discussions (negotiations, arguments) over poorly worded provisions. Just picking up the words from a letter of intent, term sheet or letter of instructions from a principal almost never works. Those information sources are both “shorthand” descriptions of the “deal” as well as merely goals agreed-upon without a full appreciation for what is already in the lease form to be used (and, in most cases, in anyone’s lease form).

For example, one can always expect that the parties have agreed on the sketchiest outline of “Landlord’s Work.” It takes time and some back-and-forth to get the details “right.” By “right,” we mean to get them written in a way that “someone who has never even heard of the deal” can definitively know what needs to be done. A close cousin is a deal term calling for the parties to “cooperate” but not to interfere with each other.

Basically, “custom” business terms, ones crafted for a particular deal and not falling into a common group of “expectable” modifications, need to be thought through and require a careful reading of the document that forms the basis for the lease. And, “careful” means re-reading the entire lease with a fresh mind. That alone calls for “waiting a day.” Otherwise, the draftsperson/re-reader only sees what she or he thought she or he “meant.” Custom business terms need to be written in a detailed fashion because they haven’t been tested through past use. They need to be mentally walked-through, and the draftsperson must run the language up against hypothetical situations. Basically, they need contemplation and contemplation takes time.

To us, this makes sense. When we use a “lease form” or draw a provision from our library, we are taking advantage of language that has been through the wringer. Often, it was written by someone else, possibly long ago. It has been “vetted” by you and those who preceded you. It has been challenged by those on the “other side.” Basically, it has passed the test of time. Newly crafted custom provisions have not. So, at a minimum, they require reflection. Often that means “tomorrow” when they are fresh again.

None of this is to suggest that the first version of a lease should take a month or a week or a day to prepare. All we are suggesting is that a well-crafted first draft will shorten the time it takes to reach a final version but will always take longer than the people waiting to see it expect or desire.

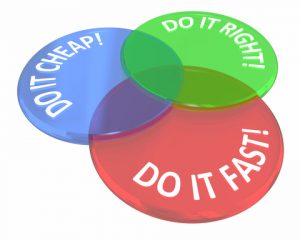

There is something called the “Project Triangle.” It suggests that of the following three criteria: Quality, Speed and Price, you can only choose two. Most people accept that premise; some don’t. If any reader is interested in a “picture” showing such a triangle and in one of many articles about the proposition, click: HERE.

If we’ve achieved one of this week’s goals, then this may be the shortest length blog posting we’ve ever foisted on readers. If not, it’s close. Don’t get used to it. This week, we’ve chosen speed and price over quality.

Ira – I’ve been doing leases for a very long time. One irritating aspect of this business is the unrealistic turn-around time expected by brokers and real estate representatives. By the time you’ve trained these people on what to realistically expect, they retire, the next younger generation of hot-shots come along and you have to start all over again. I always remember the adage that “there is never enough time to get the document right the first time out the door but always plenty of time to waste later on in correcting it.”. I try to carefully capture as much as I can in the first draft as it will save time in the negotiating process down the line. That said and while starting with a form lease and having to come up with unique clauses for unique situations, I think it is reasonable to get out a first draft in 1-2 days. get a first draft . Re your comment about AI production of several drafts, not just the initial draft – I just don’t buy it. How does the process of negotiating from that draft work, considering all of the human nuances involved, when dealing with a “HAL-9000” opponent?

Yea, but AI will never write real estate lease “extensions”. Why, you ask? Well, . . .

AI will be writing new real estate leases 5 years from now.

The planet will be devoid of life 5 years after that. So . . .

. . . there won’t be any real estate lease extensions for AI to write.

(I might as well leave the office early.)

Better right than quick.

Careful crafting from the start of custom provisions to describe unique property and occupancy circumstances is paramount if one hopes to arrive at language agreement without laborious back and forth. In order to be most effective, such initial crafting depends upon the crafter having sufficient experience with WHAT HAPPENS IN PROPERTIES AND HOW PEOPLE ACT. That experience forms the basis of the perspective required to anticipate and identify (as much a possible) what may happen and how people may act in any given circumstance. Absent that experience, and that of negotiating complex occupancy and use concepts, a poorly drafted provision that fails to address actions or circumstances that may be reasonably anticipated leads to a protracted exchange of language offers and counter-offers.