We think this comes up much too often, and, it is often about rent, more often about additional rent, and sometimes it is about a non-monetary issue. What is “this”? “This” is about when a lease says one thing and the parties, over a long period of time, do another. We bring this up today because we just read a June 6, 2019 decision by the District of Columbia Court of Appeals.

We think this comes up much too often, and, it is often about rent, more often about additional rent, and sometimes it is about a non-monetary issue. What is “this”? “This” is about when a lease says one thing and the parties, over a long period of time, do another. We bring this up today because we just read a June 6, 2019 decision by the District of Columbia Court of Appeals.

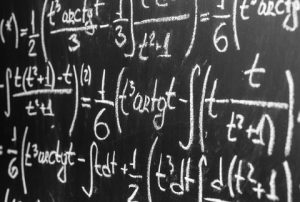

A long-term air rights lease called for rent to change every five years beginning on the 10th anniversary of the “Lease Commencement Date.” The lease provided that the new rent [that’s what the court wrote, but we all know what it meant to say as that the amount of the “rent increase“] would be the current rent:

multiplied by twenty-five percent of a fraction, “the numerator of which is the CPI at the date of adjustment and [ ] the denominator of which is the CPI at the immediately preceding date of adjustment[:]”

By the tenth grade we were taught to convert that text to the following formula: [Read more…]

Print “A committee is a cul-de-sac into which ideas are lured and then quietly strangled” — Sir Barnett Cocks. Much the same can be said about the documents we read and, sadly, write. Sir Cocks didn’t necessarily mean only that ideas were strangled to death. We want to think he also was thinking about damaged survivors, the ones that survived, but with a life-long injury.

“A committee is a cul-de-sac into which ideas are lured and then quietly strangled” — Sir Barnett Cocks. Much the same can be said about the documents we read and, sadly, write. Sir Cocks didn’t necessarily mean only that ideas were strangled to death. We want to think he also was thinking about damaged survivors, the ones that survived, but with a life-long injury. Is it masochistic to want to read court decisions? Given that most of society frowns upon masochists, it’s probably good that very few of us who create transaction documents actually read any such decisions. [That’s sarcasm.] It seems to us that what we do is engage in some “on the job training,” but mostly we rely on the wisdom of our ancestors – those who wrote the documents we use as templates. If today’s blog posting were a sermon then, fortunately, we’d be preaching to the choir. You, our readers, by being such and, almost certainly, by your reading of more erudite materials than these postings, are, unfortunately, the exception in our chosen field. Today, Ruminations salutes you.

Is it masochistic to want to read court decisions? Given that most of society frowns upon masochists, it’s probably good that very few of us who create transaction documents actually read any such decisions. [That’s sarcasm.] It seems to us that what we do is engage in some “on the job training,” but mostly we rely on the wisdom of our ancestors – those who wrote the documents we use as templates. If today’s blog posting were a sermon then, fortunately, we’d be preaching to the choir. You, our readers, by being such and, almost certainly, by your reading of more erudite materials than these postings, are, unfortunately, the exception in our chosen field. Today, Ruminations salutes you. We don’t know if there are more ways to write a purchase option in a lease “wrong” than right,” but we do know opportunities abound. Here are a couple of examples. The first is based on a statement of California law within a court opinion from March of 2018. [See it by clicking:

We don’t know if there are more ways to write a purchase option in a lease “wrong” than right,” but we do know opportunities abound. Here are a couple of examples. The first is based on a statement of California law within a court opinion from March of 2018. [See it by clicking:  Sometimes a party has the right to withhold its consent when the other party requires that party’s consent. And, sometimes the right to deny consent is desired to be absolute and unconditional. In such cases, and for a very long time, Ruminations has been using a formulation saying that such consent “may be withheld for any reason or no reason at all.” We just read a June 28, 2019 Supreme Court of Texas decision possibly chastising us for wasting those words. After analyzing a contract provision stating simply that a party could not assign its rights “without the express written consent” of the other, that court wrote that the added words, “for any reason or no reason,” were surplusage. As that court wrote, consent-required provisions with or without the extra words have identical meaning. Accordingly, “the same can be said” as to a provision reading that consent “can be granted or withheld at [a party’s] sole discretion.”

Sometimes a party has the right to withhold its consent when the other party requires that party’s consent. And, sometimes the right to deny consent is desired to be absolute and unconditional. In such cases, and for a very long time, Ruminations has been using a formulation saying that such consent “may be withheld for any reason or no reason at all.” We just read a June 28, 2019 Supreme Court of Texas decision possibly chastising us for wasting those words. After analyzing a contract provision stating simply that a party could not assign its rights “without the express written consent” of the other, that court wrote that the added words, “for any reason or no reason,” were surplusage. As that court wrote, consent-required provisions with or without the extra words have identical meaning. Accordingly, “the same can be said” as to a provision reading that consent “can be granted or withheld at [a party’s] sole discretion.” What is a “reasonable time” for something to happen or to get done? Do we ask this question of ourselves when we use that phraseology in our leases and other agreements? We can’t avoid using concepts such as “reasonable,” “material,” “promptly,” and the like, but are we being as careful as we should be when sprinkling them around?

What is a “reasonable time” for something to happen or to get done? Do we ask this question of ourselves when we use that phraseology in our leases and other agreements? We can’t avoid using concepts such as “reasonable,” “material,” “promptly,” and the like, but are we being as careful as we should be when sprinkling them around? Are waivers enforceable? It depends. How unsatisfying is that answer? Generally speaking, absent duress or coercion, parties can waive what would otherwise be their right. How does one know if there is (was) coercion? Well, some situations, such as an actual gun to the head, are easy to identify. Others are not so simple. When it comes to agreements between commercial parties, there is a presumption that they are grown-ups, able to protect their own interests. The “bigger” they are, the less likely a cry of “coercion” will rule the day. Representation by an attorney will dull a party’s claim that it was improperly forced to agree to a waiver (or other contract terms). When courts reject a party’s plea that it was coerced, you’ll often see the “deal” as having been between “sophisticated parties that negotiated at arm’s length with apparent care and specificity, and represented by competent counsel.” All of those factors concern themselves with the character of the parties and how they arrived at their agreement.

Are waivers enforceable? It depends. How unsatisfying is that answer? Generally speaking, absent duress or coercion, parties can waive what would otherwise be their right. How does one know if there is (was) coercion? Well, some situations, such as an actual gun to the head, are easy to identify. Others are not so simple. When it comes to agreements between commercial parties, there is a presumption that they are grown-ups, able to protect their own interests. The “bigger” they are, the less likely a cry of “coercion” will rule the day. Representation by an attorney will dull a party’s claim that it was improperly forced to agree to a waiver (or other contract terms). When courts reject a party’s plea that it was coerced, you’ll often see the “deal” as having been between “sophisticated parties that negotiated at arm’s length with apparent care and specificity, and represented by competent counsel.” All of those factors concern themselves with the character of the parties and how they arrived at their agreement.  Today, we begin with a French lesson. The French word, “renvoi,” means “to return,” in the sense of “sending back.” In law, “Renvoi” is a doctrine, and what follows is why you’ll be pleased to know that.

Today, we begin with a French lesson. The French word, “renvoi,” means “to return,” in the sense of “sending back.” In law, “Renvoi” is a doctrine, and what follows is why you’ll be pleased to know that.

Recent Comments