Our plan for today is to bring some insurance information to the attention of the readers of Ruminations and quickly move on to the rest of our day. So, here’s a warning. Today’s posting will be of immediate interest to a handful (if that) of our thousands of weekly readers. On the other hand, almost all readers will have heard of this first by continuing on, and we’re sure that, as these products are developed, they will solve more and more common problems. Pretty mysterious, huh?

Our plan for today is to bring some insurance information to the attention of the readers of Ruminations and quickly move on to the rest of our day. So, here’s a warning. Today’s posting will be of immediate interest to a handful (if that) of our thousands of weekly readers. On the other hand, almost all readers will have heard of this first by continuing on, and we’re sure that, as these products are developed, they will solve more and more common problems. Pretty mysterious, huh?

Let’s give this pretty newish insurance coverage a name: “Gap Insurance.” Granted, we’ve borrowed that name from the automobile leasing industry, but the name will prove to be pretty descriptive (after we’ve described the product). Some in the insurance industry are using that moniker as well.

Here’s the problem this new real estate property insurance product is aimed to solve – a lender underwriting problem.

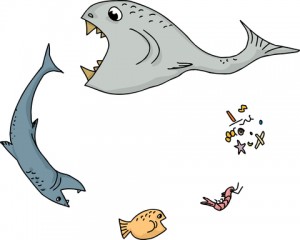

Lenders like to get all of their loan advances back, with interest on top of that. The lower the interest rate for a loan, the less risk a lender is prepared to accept. There is a kind of food chain in the lending industry. The (resuscitated) CMBS (securitized loan) market is probably a leading example of how risk and reward are related.

Over the past six or more years, the CMBS people have been battered by the marketplace over their slice and dice methods that create tranches able to yield numbers like 18% when the underlying debtor is only paying interest at 4.35%. The investors at 18% took a beating in the most recent economic turmoil (had you heard about the turmoil?). What wasn’t very well discussed was the most solid tranche, the “A” piece, that got (say) a 4.15% return on a 4.35% loan.

Holders of the “A” piece were willing to trade peace of mind for a lower return – they sought safety and a structure that would protect their principal investment (and return it intact) at the end of the loan. They also wanted to get their expected return, month after month. So, various devices were created to protect these low-risk, “I want certainty,” investor-lenders against such things as pre-payment. That’s how things like yield maintenance formulas or defeasance (look it up if this is an unfamiliar concept) came about.

Traditionally, one risk that could not be covered was a shortfall between property insurance proceeds or condemnation awards and what remained to be paid on the loan. Since CMBS loans are non-recourse loans (as far as credit risk goes), if there were a crippling, leases-ending fire or governmental taking, the lender could come up short. Lenders don’t like that.

Some properties may not be fully insurable against all casualties. Some risks are not fully covered (think, terrorism or where the land value is a significant part of the collateral. Insurance companies could fail or refuse to pay what the insured (or its lenders) believe to be the “full recovery” amount. Sometimes a leasehold mortgagor (that’s the ground tenant who borrows against its interest in the ground lease) has to share the proceeds with the ground landlord and the leasehold mortgagor’s share of proceeds or award won’t cover the balance of the loan. Sometimes the loan is based on the rental stream from a really, really creditworthy tenant, but the nature of a fire or the nature of an eminent domain taking allows the tenant (even of a really, really absolute net lease) to terminate the lease. Those are some examples of situations that increase the risk to a lender. Even if this risk is “priced in,” no one want to take comfort that they were earning five basis points for those risks when the loan payments actually do stop.

Now, to the information we promised and why we think this is good to know even outside of the world of CMBS loans.

There is now insurance to protect lenders against a gap between the amount of a condemnation award and the remaining loan balance, as well as against a similar gap if an insurance award doesn’t cover the loan balance. Right now, these policies appear to come from only two carriers (a note about that later), and only protect lenders. The policies are designed for the situation where either a credit tenant’s lease can be terminated by reason of a casualty or where buildings can’t be restored. Basically, the insurance company pays the loan and takes over the mortgagee’s position.

Today, premiums run from 1/2% to 1% of the loan amount and are paid on a one-time basis for a policy term that runs concurrently with the mortgage. Our experience is that the insurance company’s risk takes into account the likelihood of an eminent domain taking, the likelihood of a total or major loss (think, a multi-building project with a reduced chance of a total loss), and premiums (and limits) are negotiable. So, the policies don’t necessarily need to be in the amount of the loan.

Here’s the “a note about this later” follow-up. Ten years ago, we at Ruminations were faced with an issue about the adequacy of a possible condemnation award for a highway taking that could have caused the loss of some pad leases along the highway. We negotiated a manuscript “condemnation” insurance policy with Lloyd’s, the specialty risk underwriter. Then, the lender relented and that’s as far as it went. At that time, these “gap” polices didn’t exist.

That “war story,” the first ever in Ruminations, is really a lead-in to the take away from today’s posting. Today’s “gap” policies are the leading edge of a new insurance solution that can be used by those who craft deals to “Get the Deal Done.” We are at the same stage as when environmental remediation and risk polices were first introduced. These were baby steps taken by one or two carriers. They were highly restrictive in their scope of coverage. Risk sharing was an important part of the pricing. Properties were “hand” inspected. The policies were (and still are) very negotiable. Over time, the marketplace for environmental policies has greatly expanded; additional risks are covered; pricing has, in large measure, matured.

Our crystal ball says to expect that the condemnation / insurance gap policies will expand in scope and the day will come when coverage may not be limited to protected lenders.

Or, our crystal ball might prove once again that crystal balls don’t work.

Leave a Reply